Discussion - ctxc

Context Compiling: ctxc and vectorless builds

February 18, 2026

Estimated read: 7 min

I keep hitting the same wall with LLM systems:

The model can do the task… but only if it has the right slice of the document.

“Just shove the whole doc into the prompt” doesn’t scale. It’s expensive, slow, and it still fails in the worst way: it misses one constraint and confidently does the wrong thing.

So I’ve been building an approach I’m calling Context Compiling.

The first piece of it is ctxc: a context compiler.

If you want the background arc before this post, start here:

- REALM: Read Edit/Analyze Loop Monitor

- Context Curation: Preliminary REALM Tests

- REALM Continuation: Local SLM Evaluation with gemma3:1b

Context compiling in one sentence

Given a document (or doc-set) and a request, ctxc walks the document like a book, extracts the authoritative rules/facts/examples you actually need, and outputs a compact Context Packet that an “executor” model can follow.

Think of it as taking unstructured text and producing a compiled artifact you can inspect, diff, cache, and test.

Why I’m calling it “compiling”

This isn’t just retrieval.

A compiler doesn’t “search.” A compiler:

- parses structured inputs

- follows a graph (imports, includes, references)

- enforces precedence rules

- produces an intermediate representation (IR)

- emits a final artifact under constraints (size/budget)

That mental model maps surprisingly well to LLM context.

Vectorless builds

A lot of RAG stacks start with embeddings + vector search. That works, but it comes with tradeoffs:

- indexing/re-indexing overhead

- “semantic drift” (good matches that aren’t authoritative)

- hard-to-debug retrieval (“why that chunk?”)

My current direction for ctxc is vectorless builds: focus on document structure and explicit relationships.

Instead of “nearest neighbor,” I want:

- headings / TOC navigation

- internal links and references

- explicit “see also” and dependency edges

- stable provenance (“this came from Section 4.2 → Example B”)

This is closer to reading the manual than searching the manual.

(Embeddings may still be useful later, but I don’t want them to be required to get reliable results.)

For the local-first evidence behind that stance, see REALM Continuation: Local SLM Evaluation with gemma3:1b.

How ctxc works (high level)

At a high level, ctxc:

- Ingests docs (Markdown is a great starting point)

- Builds a navigation graph (headings, links, references)

- Uses a small model as a policy to decide what to pull next (“go here”, “follow that reference”, “extract this rule”)

- Packs the result into a strict token budget

The output is not “a long paste.” It’s a Context Packet.

The Context Packet (the thing that matters)

The key idea is: the context should be an artifact, not a blob.

A packet can be as simple as:

- Constraints (MUST / MUST NOT)

- Facts / Canon (do not contradict)

- Procedures / Steps

- Definitions

- Examples (short, high-signal)

- Formatting requirements

- Provenance (where each item came from)

Once you have this, you unlock a toolchain:

trace: why did we include this item?diff: what changed between two compiles?lint: did the executor violate a MUST rule?cache: reuse packets, incrementally rebuild when docs change

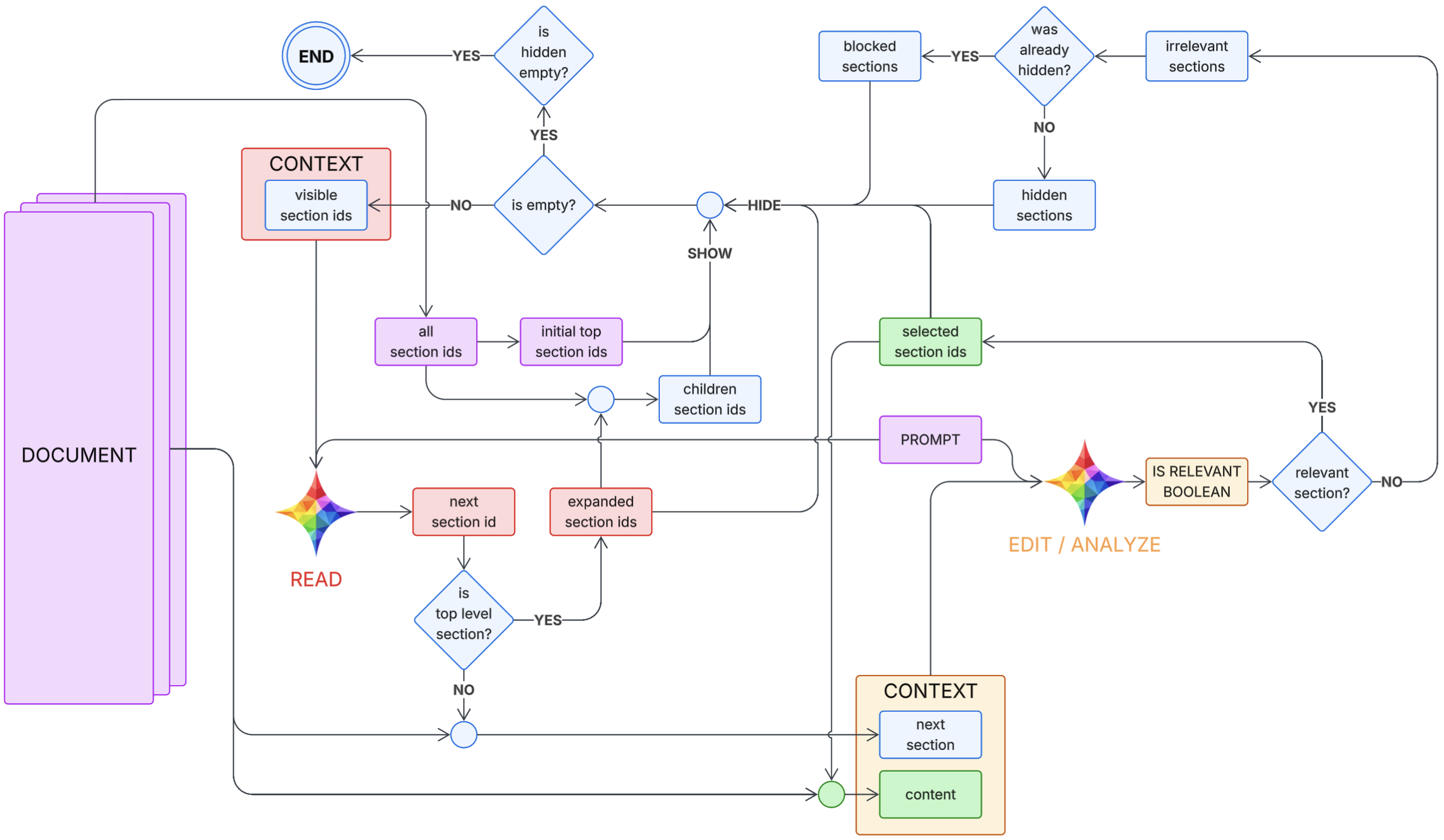

Where REALM fits

This work is designed around the same loop I’ve been exploring in REALM: Read Edit/Analyze Loop Monitor:

- (input): the task + the document (purple)

- Read about what the task needs (red)

- Edit/Analyze the current sections (orange)

- Loop and refine the context (blue)

- Monitor the context to ensure on track or if needs to exit (green)

ctxc is the practical “compiler” implementation of that loop.

Here is a sketch of how the core loop might look in code:

def run(prompt, doc):

# Document API assumptions:

# - doc.top_level_ids() -> list[str]

# - doc.children_ids(section_id) -> list[str]

# - doc.read_content(section_id) -> str

# - doc.read_all_content(section_ids) -> str

visible = set(doc.top_level_ids()) # "visible section ids"

expanded = set() # prevents re-expanding the same parent

hidden = set() # hidden once (eligible for second look)

blocked = set() # hidden twice (final exclude)

selected = set() # OUTPUT: relevant ids

visited = set() # loop protection

while True:

# Termination / resurfacing

if not visible:

if not hidden:

break # END

# SHOW: resurface hidden candidates for a second pass

visible |= (hidden - blocked)

# READ model chooses next id using only (prompt, visible)

next_id = READ(prompt, visible)

# Loop protection: if we ever revisit an id, exit (architecture invariant broken)

if next_id in visited:

break # or raise RuntimeError(f"READ returned already visited id: {next_id}")

visited.add(next_id)

# Defensive: if READ returns something not visible, drop it and continue

if next_id not in visible:

continue

# Consume this choice so READ cannot pick it again immediately

visible.remove(next_id)

# Expand if it has children (do not run EDIT/ANALYZE on non-leaf)

children = doc.children_ids(next_id)

if children:

if next_id not in expanded:

expanded.add(next_id)

# SHOW children, but do not re-add anything already hidden/blocked/selected

visible |= (set(children) - hidden - blocked - selected)

continue

# Leaf section: run EDIT/ANALYZE

next_content = doc.read_content(next_id)

content = doc.read_all_content(selected) # all selected content so far

is_relevant = EDIT_ANALYZE(prompt, next_content, content)

if is_relevant:

selected.add(next_id)

hidden.remove(next_id) # if it had been hidden before, clear it

continue

# Irrelevant leaf: HIDE / BLOCK logic

if next_id in hidden:

# Second strike -> BLOCK, and remove from hidden as requested

hidden.remove(next_id)

blocked.add(next_id)

else:

# First strike -> HIDE

hidden.add(next_id)

content = doc.read_all_content(selected) # all selected content so far

is_done = MONITOR(prompt, content)

if is_done:

break

return selected

Related posts in this same thread:

Why this is exciting for coding tools

Coding assistants fail less when they have:

- the exact API contract

- the real configuration rules

- the sanctioned usage patterns

- the “do not do this” list

Instead of shipping an entire README into a prompt, ctxc can compile:

- auth + security rules

- endpoint shapes

- error handling expectations

- canonical examples

…and then hand a clean packet to the executor.

Why this is even more exciting for writing books

Writing isn’t “just prose generation.” It’s constraint satisfaction over canon:

- timeline continuity

- what each character knows (knowledge boundaries)

- voice and POV rules

- delayed reveals

- promises and payoffs

A story bible is just another document—except continuity mistakes are painful.

A context compiler can emit a scene-ready packet like:

- “Here is who everyone is right now”

- “Here is what cannot be revealed yet”

- “Here are the motifs/tone constraints”

- “Here are continuity watch-outs: spellings, titles, geography”

That’s the path to making the executor model small too:

the compiler carries the structure; the tiny model carries the pen.

Implementation direction

I’m leaning toward building ctxc as:

- a Rust library (fast, portable, local-first)

- a CLI (

ctxc compile,ctxc trace,ctxc diff,ctxc lint) - later, a GUI for managing projects and watching compiles live

Local-first matters—especially for authors.

The end goal

The goal isn’t “bigger prompts.” It’s the opposite:

Smaller, higher-quality prompts—compiled, explainable, and testable.

And once the compiler is reliable, the executor can be much smaller too.

What’s next

I’ll likely follow this post with:

- a concrete Context Packet schema

- how I represent document structure (headings/links/references)

- caching + incremental compilation

- a first “scene packet” prototype for writing